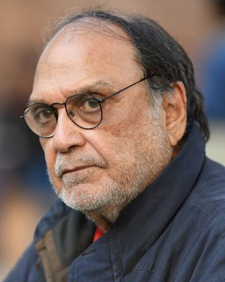

Khaled Ahmed

On November 14, Prime Minister Imran Khan repeated himself on the unwisdom of Pakistan “fighting others’ wars” instead of presumably its own which it dodged. He added that “Pakistan would no more join any alliance for any other country’s war” but “rather play the role of a reconciler or bridge-builder”. The occasion was the concluding session of The Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI)’s Margalla Dialogue 2019 held in Islamabad.

He referred to the Afghan jihad of the 1980s and the American “war on terror” following the 9/11 crisis. He regretted that the “foreign funding” that flowed into Pakistan’s coffer in return for fighting these wars was nothing compared to the cost paid in the shape of social disaster: “The impact on society is yet to be analysed”.

Prime Minister Khan is right in saying that no state busy attaining its fundamental developmental targets should ever think of war – which requires limitless realism and rejection of nationalism and its adjuncts of pride and conquest. The truth is that Pakistan has fought certain wars as an “aligned” state when in dire need of financial help. And it has fought certain other wars that its allies in the West didn’t like, and yet it failed to avoid the kind of fallout that Khan wishes to avoid. It is moot whether the wars it didn’t fight for its Western allies were less damaging than the “patriotic” wars it fought for its own cause.

The practical truth is that when Pakistan fought “others” wars, it got some money for the material and spiritual damages it suffered; but when it fought its own wars it didn’t get any money from anywhere, and the damage it suffered stayed with it as fallout from historical blunders. Khan opposes Pakistan’s decision to take part in the post-9/11 war in Afghanistan in 2011 which took place under a Chapter 7 resolution of the UN Security Council on which India, like the rest of the world, had consented to become an ally.

An “international army” of “terrorists” was prepared with American and Saudi funds, and Pakistan, in Khan’s words, “trained” this army in terrorism. The irony is that when Pakistan finally turned on its own terrorist outfit called Taliban, Khan and his party sided with the Taliban and he was “chosen” by it as its “vakil” (legal representative). Then Pakistan was getting out of a war of “others” by getting rid of the Taliban, but Khan didn’t like it.

Then there were wars fought by Pakistan as “Pakistan’s own wars” with disastrous results and no international support. No money came in; no comfort was derived either from the fact that they were driven by nationalism. It fought the 1965 war against India based on its “moral” stance on Kashmir. It used the weapons it had got from the Western allies for fighting the Soviet Union and thus lost their international support. There is no evidence that this “national” war against India gave Pakistan any advantage in its internal development. There is however evidence that the 1965 war actually sowed the seeds of disagreement between its two wings leading, in 1971, to the fall of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh.

The ironies springing from Pakistan’s “own wars” are hard to stomach as we blame “other states” for what happened even in this case. The common denominator in the military defeats suffered by Pakistan is the dominance of the Pakistan Army and a succession of martial laws. This dominance continues and Prime Minister Khan will have to rethink his wisdom about wars in 2019.

The last war which Pakistan fought as its own war and not “for American money” was the Kargil war of 1999. It was a defeat more humiliating than the 1971 war that broke up the state. Taking place between May and July 1999, the Kargil conflict was a disaster. But there was “habitual” damage in the aftermath. Instead of stock-taking and self-correction, this “national war” strengthened the very elements who had undertaken this stupid misadventure.

But rather than face punishment for his failings, its planner-executioner, then-Army chief General Pervez Musharraf, staged a coup against the democratically elected government of Nawaz Sharif in October 1999, grabbing the reins of power for nearly a decade. An already crippled economy, struggling under the weight of sanctions imposed by the US after the previous year’s nuclear tests, had to cough up $2 billion for the botched war. The damage to Pakistan’s international standing was no less significant: in the eyes of the world, Pakistan was now a dangerously unstable state led by brainless military officers with little or no accountability.

Conclusion: Fighting any wars in this day and age is disastrous for the state but fighting others’ wars still comes out better than fighting the “patriotic” ones that drain the state of funds and lose international support. Prime Minister Imran Khan has however turned a new leaf by calling out to India to start cross-border trade and “normalisation” of relations. This means eschewing all kinds of wars – even though fighting “others’ wars” still looks a bit more attractive than Pakistan’s “own wars”.

♦