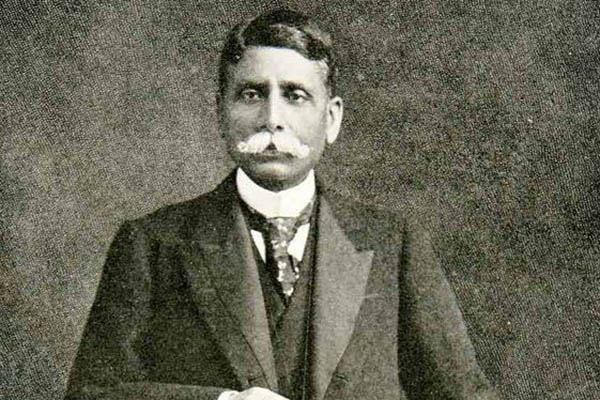

An expert in Islamic law, the Bengali scholar paved the way for the political training of Muslims in India

by Khaled Ahmed

One must give credit to Dr. Sikandar Hayat, Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at FC University Lahore, for writing a most detailed portrait of great Islamic scholar Syed Ameer Ali—seldom discussed in Pakistan—in his book, A Leadership Odyssey (OUP 2021).

Syed Ameer Ali’s books were highly influential in Pakistan in the years following the Partition of 1947, but no one knew who he really was. Now we know that he was a Bengali Muslim who lived in England and championed the cause of Muslims in India. In 1873, at the age of 24, he had authored A Critical Examination of the Life and Teaching of Mohammad (PBUH), which was the first book ever on the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and Islam in English by a Muslim author. This book was later revised and expanded into The Spirit of Islam (1891).

The book exercised a much wider influence on the international audience, produced several editions, and became one of the most authoritative works on the subject. In 1899, Ameer All’s popular book on Islamic history, A Short History of the Saracens, was published. He was also considered an authority on what was then called Muhammadan Law (Islamic Law), authoring two volumes on the subject. The first draft of his Personal Law of the Muhammadans later formed the second volume of his work in Muhammadan Law, and was written during his stay in England, 1879-80.

A genius of Bengal

Ameer Ali was born on April 6, 1849 in Chimsurah, on the banks of Hooghly River in Bengal. He traced his descent from Islam’s Prophet through his daughter, Hazrat Fatima, and claimed that his ancestors had moved to India and settled in Oudh in a prosperous township. His father, Saadat Ali, was a first-class Arabic and Persian scholar and toward the end of his life had been working on a history of Islam’s Prophet. Ameer Ali went on to attend Hooghly College and was one of the first Muslim graduates; he pursued his Master’s degree in history, followed by a degree in law (LLB), which helped him win a government scholarship to go to London for his Bar-at-Law. He was called to the Bar in 1873 and was to marry Isabella Ida Konstan there in 1884.

Upon his return to India, Ameer Ali got himself enrolled as an Advocate of the High Court of Calcutta and started his practice primarily as an expert in Muslim law. Given his command over Arabic and Persian, having been tutored early in life by his scholarly father, this expertise even got him a part-time lectureship in Muhammadan Law at the University of Calcutta. However, he soon abandoned private practice, and in 1877, was persuaded by the government to accept the permanent position as a presidency magistrate. In 1890, he was appointed judge of the Bengal High Court, the second Muslim High Court judge in India after Justice Syed Mahmood, son of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Syed Ameer Ali retired from service in 1904. He decided to move to England and settle in London, perhaps in deference to his English wife, Isabella Ida Konstan, who wanted to go back home.

Ameer Ali and Muslim politics in India

Ameer Ali and Syed Ahmad Khan knew each other well and had met in England and India both. As Ameer Ali recorded in his memoirs, they “had frequent opportunities of discussing the position of the Muslims and of their prospects in the future.” But they disagreed on the approach. Syed Ahmad Khan pinned his faith on English education and academic training; Ameer Ali admitted their importance but urged that political training, too, should proceed on parallel lines with that of their Hindu compatriots as they were certain to be submerged in the rising tide of new nationalism. Sir Syed would not admit the correctness of Ameer Ali’s forecast but after the birth of the National Congress came to realize the importance of this “political training.”

There was however a perceptible political rivalry between the two leaders, both trying to lead the Muslims in their own ways and from their own separate and unique constituencies (Syed Ahmad Khan in the United Provinces (UP) and Ameer Ali in Bengal). Thus, at times, they were not in harmony and accord with each other.

National Muhammadan Association

The Muslims of Bengal had no choice other than channelizing their economic discontent into self-reliant political action through a political organization capable of aggregating and articulating their interests as a community, as opposed to the Hindu community, which was already active under the banner of the Indian National Association led by Surendranath Banerjee. While Ameer Ali quickly grasped the point, his erstwhile senior in Bengali politics, Nawab Abdul Latif, like Syed Ahmad Khan in the UP, kept on insisting on the pursuit of English education as pre-requisite of any political activity lest it deflect Muslims from “the path of Education and Loyalty.” Nawab Abdul Latif failed to carry conviction in the milieu of 1878. And Syed Ahmad Khan likewise failed to make any deep impression on the Bengali Muslim, thus leaving the political field to Ameer Ali to represent their interests and indeed, eventually, the entire Muslim community through his newly-founded National Muhammadan Association.

Both Abdul Latif and Syed Ahmad Khan continued to contest Ameer All’s political stance and leadership. Abdul Latif represented the old guard, with influence and experience, having established the Muhammadan Literary Society into an influential nucleus of educated elite—mostly conservatives. He saw Ameer Ali’s Muhammadan Association as a threat to his leadership, even in the education campaign. Thus, there emerged a kind of personal rivalry between the two, to the extent that neither he nor his conservative ultra-loyal friends had any sympathy for Anglicized Muslims like Ameer Ali who in their eyes had ceased to share the ways of life of the Muslim community.

Ameer Ali and All-India Muslim League

Politically, the most significant contribution of the Muhammadan Association was its Memorial of 1882, authored by Ameer Ali, and submitted to the Muslim community. Lord Ripon had constituted a commission to suggest the reform of education and employment opportunities in the country. Ameer Ali, of course, expanded its scope to project Muslim demands and aspirations at a national level.

Ameer All’s plea for a central organization of the Muslims found fulfilment in the form of the All-India Muslim League on Dec. 30, 1906 at Dacca (Dhaka). He welcomed it wholeheartedly as it was to bring Muslims in touch with the thinking in England. He hastened to form its London branch, where he was fully settled, dubbing it the London Muslim League and formally launching it on May 6, 1908. The London Muslim League went on to play a crucial role in securing for Muslims the right of separate electorates in 1909, through the Morley-Minto reforms.

On Jan. 27, 1909, Ameer Ali led a delegation of the London Muslim League to meet with Morley to convince him of the genuineness of the Muslim demand for separate electorates. However, Ameer Ali himself could not maintain loyalty to the Muslim League for long. He severed his connection with the All-India Muslim League in 1913, for several reasons. One was the repeal of the Partition of Bengal in December 1911, and the unhelpful British attitude toward Turkey in the Turco-Italian war. The good old fabric of Muslim loyalty was beginning to crumble.

Resignation from Muslim League

Maulana Mohamed Ali Jauhar, a Pan-Islamic leader, led the charge against the British in a defiant mood. More importantly, Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s entry into the Muslim League, with the demand of self-government in India, made the situation all the more precarious. Ameer Ali, like the Aga Khan, did not feel comfortable with this new policy as he saw it rather advanced, and, in part, even extremist. The result was that, in October 1913, after finding himself unable to work under the conditions now demanded, he resigned from the presidency of the London Muslim League and also ceased to be an active representative of the All-India Muslim League in London.

The Indian Muslims, having launched the Khilafat Movement led by Maulana Mohamed Ali and other Muslim leaders, were soon joined by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and other Congress leaders through the Khilafat-non-cooperation movement. The development was borne of deep concern with the fate of Ottoman Turkey, because the institution of Khilafat rested in that country, with the Khalifa being the spiritual head of the Muslims, especially Sunni Muslims. Although himself a Shia, Ameer Ali “subscribed to the Sunni theory of the caliphate and thus was keen to protect and preserve it for the good of all Muslims.”

Author Hayat concludes: “Syed Ameer Ali was reported to be the first Muslim to use the English word ‘nation’ for the Muslims of India. He helped the Muslim separatist political movement come a long way, confident and consolidated. Muslim separatist leader Maulana Mohamed Ali, of course, went on to desist and derail this movement and thus any claim on Muslim nationhood through the Khilafat-non-cooperation movement. But he soon returned to Syed Ameer Ali’s fold, realizing the futility of a Hindu-Muslim alliance for the benefit of Muslims.”