Taliban gunmen stormed a military-run school in Peshawar a year ago and, during a rampage that involved taking 500 children hostage, killed more than 140 people. Since that massacre, the Pakistani military has intensified its campaign against the Taliban.

-

The good news is that terrorist violence in Pakistan has decreased, and civilian deaths from terrorism are down about 50%. As of mid-December, according to the South Asia Terrorist Portal database, about 900 civilians had been killed in terrorist violence this year, compared with nearly 1,800 in 2014. The Pakistani Taliban, for many years the most formidable anti-state terrorist group in the country, is weakening.

But other types of terrorists are poised to step into the vacuum. Pakistan appears be moving toward an era of militancy marked less by violent anti-state groups than by violent anti-society groups. In effect, insurgency is giving way to intolerance.

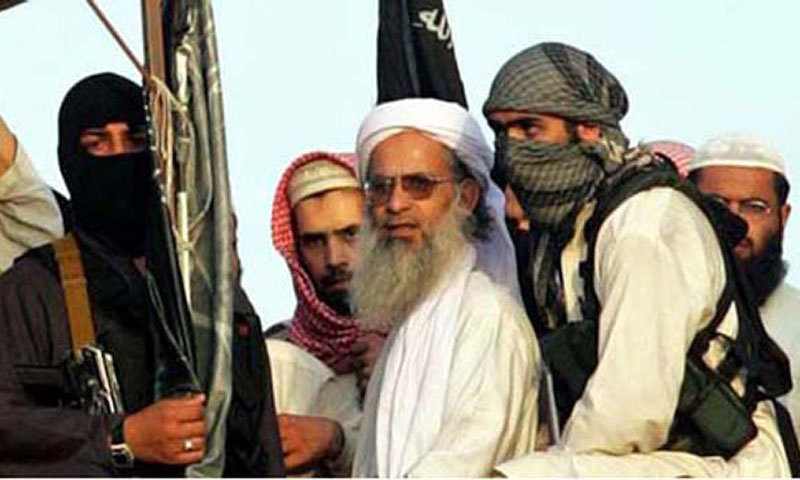

To its credit, Pakistan has taken some modest steps this year to curb hate speech and hard-line ideologies. But its society remains ripe for radicalization. Extremists such as Hafiz Saeed, the head of Lashkar-e-Taiba, which waged the 2008 attacks in Mumbai, and Abdul Aziz, the firebrand cleric of the Red Mosque in Islamabad who refused to condemn the Peshawar school attack, roam free and broadcast their views.

Sectarian hatreds and violent opposition to religious minorities are particularly pronounced. Fatalities from terrorist violence have decreased, but more people died in sectarian violence as of Nov. 15 than did last year (though the 2015 and 2014 tolls are lower than that of 2013). As of Nov. 30, there had been at least two deadly incidents of sectarian violence every month this year. Because many incidents are likely to go unreported, the true number is probably much higher.

With the Pakistani Taliban fracturing, disaffected members could transfer their allegiances to Islamic State, heightening the risk of violence against Pakistani Shiites and other minorities.

Pakistan’s climate of intolerance and the extremist ideologies that emanate from it could radicalize people from all walks of life, not just the poor. The murder of Sabeen Mahmud, a prominent human rights activist, in April shocked people in and outside Pakistan. A wealthy young man who attended one of Pakistan’s most prestigious universities confessed to the shooting. In a jailhouse interview with Pakistan’s Herald magazine earlier this year, Mr. Aziz hinted at several reasons he decided to kill Ms. Mahmud, including her “liberal, secular values” and her support for the celebration of Valentine’s Day in Pakistan.

To be sure, intolerance is an issue outside Pakistan, too. From neighboring India to the U.S. and many nations in between, ugly rhetoric and violent acts of discrimination have become the norm.

In Pakistan, however, the nastiness plays out in an environment that has long enabled extremism. Mosque leaders and school textbooks preach hard-line narratives; Saudi financing propagates hard-line Wahhabi and Deobandi Islamic beliefs; and the state often cracks down on dissent.

Pakistani authorities trying to combat violent extremism face a Sisyphean-like task: The Pakistani Taliban may be on its last legs, but the underlying ideologies of hate that fueled its reign of terror endure, and other terror groups will be happy to appropriate these beliefs for their own purposes.

Michael Kugelman is senior associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He is on Twitter: @michaelkugelman.