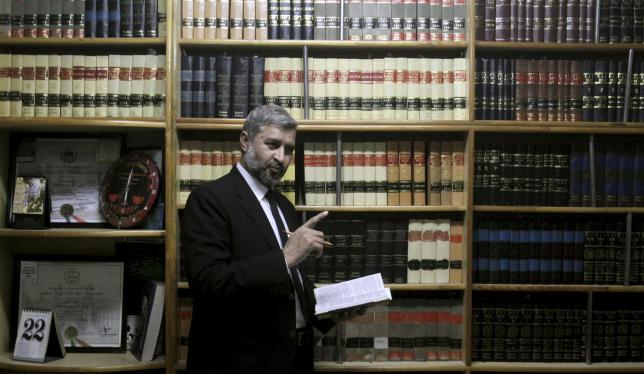

Leader of the Khatm-e-Nubuwwat Lawyers’ Forum, a conservative alliance of lawyers offering free legal advice for anyone filing a blasphemy case, Ghulam Mustafa Chaudhry poses for a portrait at his office in Lahore, Pakistan February 22, 2016. Picture taken February 22. To match Insight PAKISTAN-BLASPHEMY/LAWYERS REUTERS/Mohsin Raza

A little-known alliance of hundreds of lawyers in Pakistan is behind the rise in prosecutions for blasphemy, a crime punishable by death that goes to the heart of an ideological clash between reformers and religious conservatives.

The group, whose name translates as The Movement for the Finality of the Prophethood, offers free legal advice to complainants and has packed courtrooms with representatives, a tactic critics say is designed to help it gain convictions.

The stated mission of the Khatm-e-Nubuwwat Lawyers’ Forum and its leader Ghulam Mustafa Chaudhry is uncompromising: to use its expertise and influence to ensure that anyone insulting Islam or the Prophet Mohammad is charged, tried and executed.

“Whoever does this (blasphemy), the punishment is only death. There is no alternative,” Chaudhry told supporters crammed into his small office behind the towering red-brick High Court building in the eastern city of Lahore.

The campaign could complicate the government’s tentative efforts to reform blasphemy legislation, a tough task in a country where support for the law is widespread.

Chaudhry was the defence lawyer for Mumtaz Qadri, executed on Monday for gunning down the popular governor of Punjab province in 2011 over his criticism of the blasphemy law.

Chaudhry argued, ultimately unsuccessfully, that the bodyguard was justified in killing Salman Taseer, because he committed blasphemy by publicly questioning the law.

In death, Qadri was a hero for many. Tens of thousands of people gathered in a park in the city of Rawalpindi for his funeral on Tuesday, showering his casket with flowers.

“He lives! Qadri lives!” supporters around the coffin cried. “From your blood, the revolution will come!”

Even discussing blasphemy is a challenge in Pakistan, and officials and activists say accusations can be used by complainants to settle personal scores and intimidate liberal journalists, lawyers and politicians.

At the same time, authorities are seeking to reduce room for abuse by insisting senior police officers are involved in cases and ruling that criticising the law does not constitute blasphemy itself.

Qadri’s execution was seen as a sign itself that the government was determined to take firmer action, and it coincides with a nationwide crackdown by the powerful military on Islamist militants and their religious allies.

Since Khatm-e-Nubuwwat was founded 15 years ago, the number of criminal blasphemy cases filed in Punjab, the group’s home base and Pakistan’s most populous province, had tripled to 336 by 2014, according to police figures.

It fell to 210 in 2015 as stricter provincial rules were applied, but critics said the number was still too high.

Chaudhry told Reuters he had personally been involved in more than 50 criminal blasphemy cases, and said his group had grown to 700 lawyers in Punjab, where the majority of blasphemy cases are heard.

“If they hear of a complaint, the lawyers will come to the person and offer to take the case for free,” said a policeman, who asked not to be named to avoid reprisals.

“Sometimes they arrive with people and encourage them to make a complaint.”

Chaudhry said his group represented almost every complainant in cases across Punjab province. Reuters could not independently confirm this.

Reuters was also unable to determine if the movement has funding or any other form of backing from a specific group or groups, but Chaudhry said its motivation was not financial.

“Everyone knows that we are the forum that does these cases voluntarily,” he told Reuters. “So they contact us and tell us that there is a case to do.”

He said member lawyers investigated cases to ensure they were genuine, although they had not found an unjustified blasphemy complaint yet.

The law dates back to colonial times, but was rarely implemented until about 20 years ago.

It states that anyone found to have defiled the name of Prophet Mohammad in writing or speech, including by “innuendo or insinuation, directly or indirectly”, should be punished with life imprisonment or death.

In 1990, that was strengthened to “death and nothing else”.

No one in Pakistan has been executed for blasphemy so far, but jails are filling up with those sentenced to death, and there have been sporadic assassinations of the accused and people involved in their defence.

At least 65 people, including lawyers, defendants and judges, have been murdered over blasphemy allegations since 1990, according to figures from a Center for Research and Security Studies report and local media.

Some recent blasphemy cases made headlines around the world, including that of Christian woman Asia Bibi, whose conviction drew international attention including from the Pope. Her case was prosecuted by the Khatm-e-Nubuwwat.

Reema Omer, legal adviser at the International Commission of Jurists, an advocacy group of lawyers and judges, said the rise in blasphemy cases was deepening fears of speaking out.

“After the launch of our report (into blasphemy legislation), we were told by hosts of TV talk shows that they have been cautioned against ‘going too far’ in their critique of the blasphemy law, especially after recent cases of blasphemy allegations against anchor persons and media houses,” she said.

Chaudhry and his colleagues sometimes arrive in court with dozens of lawyers and supporters, say defence attorneys.

“Their conduct in these cases is … intimidatory, 100 percent,” said defence lawyer Saif-ul-Malook, who said he had defended blasphemy cases in courtrooms full of supporters of the forum.

In one case, a crowd of lawyers left him barely any space to stand and shouted slogans when he spoke to the judge to present his case.

Chaudhry denied the accusations, saying that he was the victim of intimidation by human rights groups, though he did not elaborate.

“We have never had any complaints,” he said.

Family members of some blasphemy defendants disagreed.

“From our side there would be one or two lawyers, but from their side there were eight or nine lawyers, 10 or 12 clerics,” said Muhammed Aman Ullah Khan, whose wife is being prosecuted for blasphemy by a complainant whose team of lawyers is led by Chaudhry.

“They said it in exactly these words: ‘If you want to be shot, then sit behind her [in court]. And if you don’t want to be shot, then may you never be seen here again.'”

Chaudhry denied the accusation.

“This has never happened. We respect the families (of the accused).”

That case is being heard at the Lahore High Court.

Last year, Punjab passed laws requiring blasphemy accusations to be investigated by a senior police officer.

But some police sources said some senior officers were reluctant to be drawn into cases, and many were still being handled by more junior staff.

“People become so emotional when blasphemy is mentioned that they want to take justice into their own hands,” said Punjab law minister Rana Sanaullah Khan.

He said some blasphemy accusations were made for ulterior motives, including the theft of land from religious minorities in the overwhelmingly Muslim-majority country of 190 million.

“The matter is often exploited … You cannot say that this (law) is exploited all the time, but it is very common,” he told Reuters.

Also last year, the Supreme Court ruled that criticism of the law did not constitute blasphemy. In January, one of the country’s most senior clerics told Reuters that he may be willing to review the law.

However, Khatm-e-Nubuwwat’s leaders oppose change, saying it could encourage violence.

“If, God forbid, this law is finished,” said forum secretary general Tahir Sultan Khokhar, “then obviously people have been given the right to decide with their own hands, to kill.”