by Tahir Qazi

Karachi is the biggest city in Pakistan. It is the country’s commercial hub, financial capital, naval base, and only operational seaport. For the past several months, this city has once again been in the grip of violence. Gunshots ringing out in poor neighborhoods claimed the lives of more than 400 individuals in the months of July and August. Poor neighborhoods house about 50 percent of Karachi’s total population, and 89 percent of the people living there are below the poverty line.

Karachi has been the scene of several waves of violence since the birth of Pakistan in 1947. Even during its quietest days over the past two or three decades, the city has always been restive.

The reasons for this violence are many and complex. They require an understanding of the demographic, ethnic, and economic politics of both Karachi and Pakistan. Given the importance of Pakistan to U.S. foreign policy, Washington should pay closer attention to the reasons for upheaval in the country’s major city.

History of Violence

The structural basis of politics and political violence in Karachi begins in the city’s demographics. The population of Karachi increased only minimally for 100 years prior to the birth of Pakistan in 1947. Within the next four years, after Karachi became the first capital of Pakistan, the population swelled 400 percent and has grown exponentially ever since. A city that housed 450,000 people in 1947 is now home to at least 18 million as of 2010.

The overwhelming influx of people from every part of Pakistan and from both adjacent and distant countries has created demographic stresses that would have broken the back of virtually any stable social system. A weak economy, underdeveloped infrastructure, and poor governance did not help build a culture of peaceful conflict resolution or social democracy. An intense competition for the political space in Karachi has challenged the rule of law – and the rules of fair play –in the social and political arena, particularly in the burgeoning shanty towns that now spread to the horizon.

In 1984, demographic pressures and ethnic competition came to a head when an ethnic Pashtun bus driver accidentally ran over a young girl named Bushra Zaidi, an Urdu-speaking Mohajir. The accident triggered ethnic violence against Pashtuns, who retaliated in kind. Within a few weeks Karachi was burning.

Urdu-speaking immigrants from India, known as Mohajirs, mainly settled in Karachi from 1947 onward. They came face-to-face with the original inhabitants of Karachi in the province of Sindh. The local inhabitants, who spoke various dialects of Sindhi, were one of the original tribes that founded Karachi. Punjabis, Pashtuns, Balochs, and others settled there over time. Now, many generations down the road, all of them have a legitimate claim that they are the rightful sons and daughters of Karachi. Ethnic tensions among Sindhis, Pashtuns, and Mohajir groups have fueled violence over the years, particularly since the Bushra Zaidi incident.

Out of the tragic accident in 1984, the Mohajirs grew to political prominence on Pakistan’s national scene. They formed a new political party currently known as MQM. Originally, the “M” in the acronym stood for Mohajir, which indicated its ethnic disposition. Today, the “M” stands for Muttahidda, or “united.” In politics, MQM has collaborated with the military and civilian administrations at the federal, provincial, and city levels. Over time, MQM has come to dominate Karachi politics through the electoral process.

The second power player in Karachi is the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), the current ruling party in Pakistan. Founded by Z.A. Bhutto, a landlord from the province of Sindh who later became prime minister, the PPP has national appeal. However, the leadership is primarily comprised of feudal land holders.

Ethnic Pashtuns moved to Karachi to earn a better living. They have affiliated with the Awami National Party (ANP). Along with MQM, the ANP appeals primarily to ethnicity.

As immigrants from India, the Mohajirs could not easily own land or command agricultural resources, and so have tended to occupy administrative, business, and middle-class jobs. MQM politics, therefore, have focused on securing the rights for ethnic Mohajirs in Karachi rather than the interests of the poor Sindhis or landowners from the Sindh province. Ethnic Pashtuns, meanwhile, have traditionally controlled the transport industry and city services.

To further complicate the sociopolitical picture, traditional religious sects and their affiliated political parties have always been active in Karachi. Religious extremism, which engulfed Pakistan after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the more recent U.S. intervention, has also had its influence in the city. Religious extremism has now coalesced in the form of militant Talibanism.

Another factor that has played a role in stirring up tensions in the city is the quota system. Historically, Karachi residents had better opportunities for education compared with those from rural Sindh. The introduction of a quota system was meant to level the field for urban and rural residents of the province. In practical terms, this policy offered opportunities to those who maintained a rural address even if they lived their whole life in Karachi. However, the system limited access for Karachi urbanites to higher education and federal jobs. Rather than taking up common issues for all Karachiites, the dominant political player, the MQM, attracted educated young Mohajirs in Karachi by stoking resentment over the quota system. .

Economics and Turf War in Karachi

As the commercial capital and the only seaport, Karachi generates huge revenues for Pakistan. According to the Federal Board of Revenue Yearbook 2006/07, Karachi accounts for 75 percent of custom duties on imports. Overall, Karachi contributes about 20 percent of Pakistan’s total GDP, and more than 60 percent of the cash flow of the Pakistani economy takes place in this city.

Karachi is the mercantile hub for virtually all transnational corporations and international banks. It is the nerve center of transport industry in Pakistan. As a port, Karachi is also close to busy sea lanes.

It serves as the port of entry for military hardware and goods for the Coalition forces in Afghanistan. The war, in other words, is good business for Karachi and for other business interests in the country. Since Karachi is the economic jugular of Pakistan, social instability in the city can cripple the economy for the whole country.

High unemployment, rampant poverty, and a sharp divide between rich and poor amplify grievances in Karachi and in the country as a whole. Add to that turf wars between various types of mafias, as well as deeply entrenched patronage systems, and Karachi becomes a veritable tinderbox of tensions.

The pattern of patronage is not exclusive to Karachi. The other provinces of Pakistan have a similar culture of favoritism and corruption that amounts to a virtual mafiacracy. In a mafiacracy, political parties, elites, police, and criminal gangs all collaborate according to a set of unwritten rules.

The strategic location of Karachi and its endemic violence has raised the ante for U.S. policy in South Asia. A local turf war among different ethnicities and their political patrons can thus have geopolitical implications. No wonder that the United States has a stake in the current turmoil in Karachi.

U.S. Policy Implications

Pakistan is central to U.S. policy in Afghanistan. If Karachi comes to a halt because of violence, the NATO mission would come under severe threat. It is simply a matter of logistics. The only alternative port in Pakistan is Gwadar, and it’s far from operational. The United States could find supply routes through the northern part of Afghanistan, but that’s not an easy option either.

So far, there have been no attacks on U.S. convoys around Karachi compared with other areas along the route. The tide could turn at any time, however, given how many competing interests lie so close to Pakistan’s economic jugular. This is truly a “wicked problem,” as social planners define challenges characterized by complex interdependencies that defy easy solutions.

U.S. policy in the region is not solely focused on Afghanistan. It also addresses overall regional stability, counter-terrorism, and nuclear non-proliferation. All of these objectives require a peaceful and progressive Pakistan.

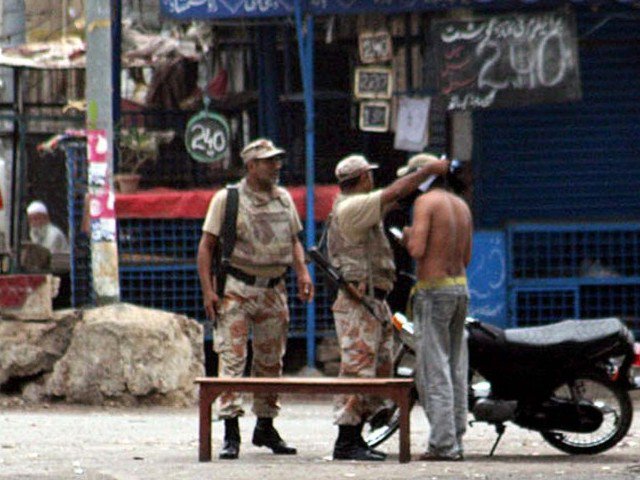

The unrest in Karachi reveals the problems inherent in Pakistan as a whole. In the short term, the restoration of law and order is the first priority. In the long term, multiple sections of the Kerry-Lugar bill of 2009 provide the United States with leverage to insist that the Pakistani government set aside political disagreements for the sake of long-term stability.

The Kerry-Lugar bill offers a broad vision and flexibility to the US policy makers to focus not only on the military targets but to work for the development of social infrastructure in Pakistan. It holds a better promise for U.S.-Pakistan relations and peace prospects in the region in general. Whether overt or covert, warfare is expensive. Peace is an economical bargain in comparison. The decade-long war in Afghanistan and the fragile situation in Pakistan, badly worsened by the war itself, makes it imperative to end this war as soon as possible.

Tahir Qazi is a neurophysiologist and contributor to Foreign Policy In Focus. He can be reached at tahir.qazi@yahoo.com.