Born Adrian Elms, raised Adrian Ajao, died Khalid Masood. Shifting identity and simmering anger put popular pupil on destructive path

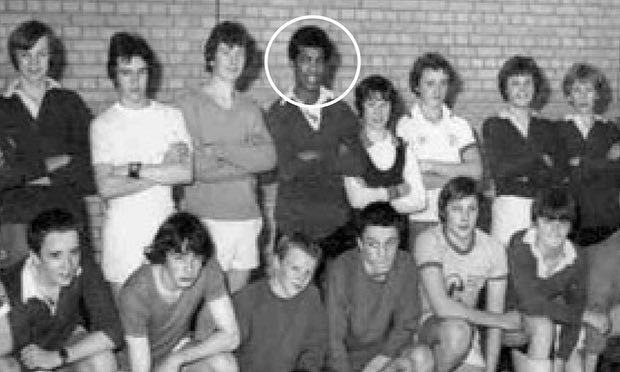

Masood – then Adrian Ajao – pictured after a 24-hour sponsored football match in his school days. Photograph: Huntleys school website

by Sandra Laville and Robert Booth

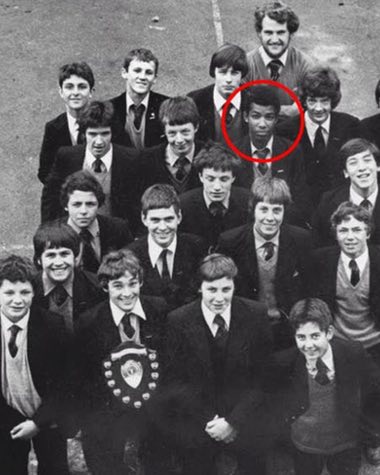

In an old school photograph, the smiling face of Adrian Ajao is a picture of a healthy, happy, middle class boy from Tunbridge Wells. Beaming with satisfaction after a football marathon, he stood on the cusp of a fruitful life.

What led that bright, sporty, popular teenager to become the Islamic State-inspired killer responsible for the attack on parliament this week confounds those who knew him then and is now the focus of a urgent and sprawling investigation by the security services.

“He was a smashing guy, really nice chap,” said Stuart Knight, an old classmate at Huntleys school. “The picture of us in the football team was after we did a 24-hour sponsored football match to raise money for the sports hall. We would have been about 14 years old. Everyone got on with Adrian, he was a lovely bloke.”

But there are themes running through the life of Adrian Ajao, who was born as Adrian Elms and who died as Khalid Masood that help explain what went so terribly wrong and turned that “lovely bloke” into the most murderous terrorist in Britain since 2005.

They include a shifting identity and a conviction, perhaps paranoid, that he was an outsider as the black child born out of marriage in the 1960s to a teenage white mother in Kent. He seemed to simmer with resentment and anger, which exploded repeatedly throughout his life in violent episodes involving knives. It was a toxic combination that found its most deadly outlet when he embraced Islamic extremism in its most violent form.

Born in Hainault maternity hospital in Erith, his mother Janet Elms was 17 when she gave birth and brought him up alone, until she met and married Philip Ajao two years later and moved to Tunbridge Wells. His two younger brothers were born in the genteel town, and the family lived in St James Park among big Victorian villas. His mother attended the local church.

“They seemed quite pleasant, just a normal family,” recalled a neighbour.

“He had a big personality and everyone liked him,” said former classmate Kenton Till. “He was very bright and very good at chemistry. I think he wanted to do something like that after he left school.”

According to Till he was known among his peers as Black Ade, a nickname that barely masked underlying racism. When he left school at 16, he lost touch with classmates and began to be drawn into the life of petty crime.

“I remember he came to a new year’s party at my house but he was with a group of lads who were drunk and on something and my parents asked them to leave,” said Tills. “After that we sort of lost touch.”

By 18, Ajao was into dealing drugs and had a notched up a conviction for criminal damage. He later skipped town with a string of debts in his wake, former friends recalled. One said he was at one point a “heavy cocaine” user who managed to hold down a job at Woolworths.

At 28, Ajao met Jane Harvey and tried to get his life back on track. The couple had a daughter in 1992 and moved to rural Sussex in search of the tranquillity. They lived in a four-bedroom detached house with a large garden in Northiam, a village near Rye, east Sussex.

He found a job in a nearby chemical company, which supplied cleaning fluids to hotels and restaurants, and began studying for a university degree. He set up his own business – but his feelings of alienation and resentment appeared to grow.

“He was very intelligent but always slightly sinister,” said Alice Williams, who knew him while landlady of the Rose and Crown pub near Rye. “He would do the Telegraph crossword and, to be fair, would make intelligent conversation but he was a bit racist. He always had a chip on his shoulder.”

In 2000 his parents, the stability in his life, moved to west Wales, where they bought a farm and his mother started making handmade cushions and bags from her farmhouse kitchen. While they settled into a rural life, their son’s attempt at country living came to a violent end.

One night in the Crown and Thistle pub in Northiam, Ajao flew into a row with a local, Piers Mott.

Leaving the pub, he used a knife that he had been using to decorate his daughter’s bedroom and slashed the seat covers on Mott’s car, shouting and gesticulating as he did so. When Mott came out Ajao cut him across the face, leaving a three inch gash on his cheek.

He was charged with unlawful wounding and possession of an unlawful weapon. He was ostracised. Ajao’s lawyer told the court: “It is a very small community and his wife and family have been extremely affected by this. He will effectively have to move his family from the village and start to live his life all over again.”

That new life was prison. Ajao pleaded guilty and was jailed for two years serving his sentence, it is understood, in Wayland prison in Norfolk.

Judge Charles Kemp told him: “The reality is that you lost your temper and went beyond the bounds of what is reasonable.”

In September 2003, by now living in Eastbourne, he was jailed again, this time for six months for attacking a man with a knife, again in the face, outside a nursing home in the town.

This time the prison culture was different. In the wake of the 11 September attacks many British extremists were in jail under new terror laws and the prison system played host to the radicalisation of new recruits. Targets for conversion were often young men with violent backgrounds struggling with their identities – men like Ajao.

Within months of emerging from prison, he had met and married a young Muslim woman working as a marketing assistant, Farzana Malik.

It seems to have been a turning point. Marriage records show he used his birth name Adrian Russell Elms but his identity was about to shift once more and Adrian Ajao, aka Elms, became Khalid Masood.

One Comment